"Forman was volatile and uncompromising, an angry young man. His head had been clubbed many times on the front lines in Dixie. He was impatient with Urban League and NAACP types; he was nervous and perhaps a trifle battle-fatigued." ~ James Farmer, Lay Bare the Heart

James Forman was born October 4, 1928 in Chicago, spending time when he was not in school with his grandparents in Marshall County, Mississippi. He graduated with honors from Englewood High School in 1947 and after a semester at a community college joined the Air Force, serving in Okinawa. He then enrolled at the University of Southern California but after being arrested outside the campus library on suspicion of robbery and being beaten while in custody he returned to Chicago. In 1954 he enrolled in Chicago's Roosevelt University, graduating in three years. He began attending graduate school at Boston University, but after being inspired by the court-ordered integration of Central High acquired press credentials from the Chicago Defender in 1958 and went to Little Rock, where as his obituary in the Washington Post stated, he "filed a few stories, worked on a social-protest novel and looked for opportunities to organize mass protests in the South."

Such an opportunity came through the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and by 1961 Forman had been named Executive Secretary of SNCC under Chairman John Lewis. His skill at organizing and directing voter registration volunteers, as well as handling administrative details, publicity, and fundraising, were what Eleanor Holmes Norton called an "organizational miracle in holding together a loose band of nonviolent revolutionaries who simply wanted to act together to eliminate racial discrimination and terror." SNCC became one of the "Big Five" civil rights groups, along with the older National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, National Urban League, Congress of Racial Equality, and Southern Christian Leadership Convention. Forman took part in organizing the August 1963 March on Washington and was responsible for rewriting Lewis's speech to make it less inflammatory. The next year he led a group of 10 SNCC members in a visit to Guinea.

As SNCC became more militant, in 1966 Lewis and Forman were replaced in office by Stokely Carmichael and Ruby Doris Robinson. Forman helped negotiate the brief merger between SNCC and the Black Panther Party, and for a time took part in Panther leadership, serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Director of Political Education. In 1969 he participated in the Black Economic Development Conference in Detroit, culminating in the "Black Manifesto" calling for $500,000,000 in reparations.

Forman continued to write and participate in the civil rights movement. In 1980 he earned a master's degree in African American History from Cornell University, and in 1982 a PhD from the Institute for Policy Studies Union of Experimental Colleges and Universities. He taught at American University and campaigned for statehood for the District of Columbia. He died January 10, 2005 at the age of 76. His son, James Forman, Jr is a professor at the Yale Law School.

LOCAL UNIT INFORMATION and

BLACK HISTORY BLOG FEATURING EVENTS AND PEOPLE CONNECTED TO TEXAS OR NAACP.

SOME DAYS ARE DATE-SPECIFIC, SO CHECK THE BIRTHDAYS!

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

"It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have." ~ James Baldwin

"Nothing in the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity." ~ Martin Luther King, Jr.

P O Box 1752 Paris TX 75461 ~ 903.783.9232 ~ naacp6213@yahoo.com

Meets First Thursday of Each Month at 6:00 PM ~ 121 E Booth

Showing posts with label Chicago. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Chicago. Show all posts

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Richard Wright

"I was leaving the South

"I was leaving the South to fling myself into the unknown . . .

I was taking a part of the South

to transplant in alien soil,

to see if it could grow differently,

if it could drink of new and cool rains,

bend in strange winds,

respond to the warmth of other suns

and, perhaps, to bloom"

Richard Nathaniel Wright was born September 4, 1908 near Natchez, Mississippi. His family moved around throughout the area, often living with relatives after his father left and his mother suffered a series of strokes. Wright, his mother and older brother settled in Jackson, Mississippi when he was eight to live with his grandmother, an extremely religious woman. The repression he experienced there, as well as the racism encountered in daily life, formed the basis for his writing throughout his life.

Wright graduated from Junior High as valedictorian but refused to give a speech written by the vice principal that catered to the all-white school board. This was the end of his formal education, and at age 15 he moved to Memphis where he began reading H. L. Mencken and other books a white co-worker checked out of the library for him. He later moved to Chicago, continuing to educate himself, reading the naturalist literature of Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Sinclair Lewis. He worked as a postal clerk, and his mother, brother and aunt came to live with him. When he was laid off in 1931 the family was forced to go on relief.

During this time Wright joined the John Reed Club, a Marxist organization for artists, writers, and other intellectuals. He joined the Communist Party in 1933 but became disenchanted by power struggles and racism in the part, as well as being perceived as bourgeois by other African Americans because of his intellect and his association with whites. His experience during this time was published in 1944 in Atlantic Monthly as "I Tried to Be a Communist".

Wright moved to New York in 1937 where he became the Harlem editor of The Daily Worker, and participated in a WPA writers' project where he won a $500 prize for his short story, Fire and Cloud. The acclaim from this win led to the publication of a collection of four novellas, Uncle Tom's Children, a brutal depiction of life in the South.

It was followed in 1940 by Wright's most noted work, Native Son, again a bleak portrayal of African American life in the early part of the twentieth century. This book, set in Chicago, explores the social forces leading central character Bigger Thomas to murder his employer's daughter. An immediate best-seller, it became the first Book of the Month Club selection written by an African American and is considered one of the most influential books of the century.

A dramatic version written by Wright and Paul Green, and produced by Orson Welles, opened on Broadway the following year. Also in 1941 Twelve Million Black Voices was published, with Wright's descriptions of photographs by Edwin Rosskan. An autobiography Black Boy came out in 1945, depicting Wright's life in the South before his move to Chicago. A second volume covering his later years, American Hunger, was published posthumously in 1977.

To escape American racism and the growing anti-Communist political climate, Wright moved to Paris in 1946, becoming a French citizen the next year. His later novels, influenced by his association with existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir, did not have the success of his earlier work. He traveled throughout Europe, Africa and Asia, writing non-fiction accounts of culture, politics and religion. He began writing haiku in the late 1950's, amassing over four thousand, with 817 published in Haiku: This Other World in 1997.

Keep straight down this block,

then turn right where you will find

a peach tree blooming.

As the sun goes down,

a green melon splits open

and juice trickles out

Coming from the woods,

a bull has a lilac sprig

dangling from a horn

The Christmas season:

a whore is painting her lips

larger than they are

Wright died suddenly in Paris of a heart attack on November 28, 1960 at the age of 52. He was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1939 and the NAACP Spingarn Medal in 1941.

I Have Seen Black Hands

I am black and I have seen black hands, millions and millions of them --

Out of millions of bundles of wool and flannel tiny black fingers have reached restlessly and hungrily for life.

Reached out for the black nipples of black breasts of black mothers,

And they've held red, green, blue, yellow, orange, white, and purple toys in the childish grips of possession,

And choclate drops, peppermint sticks, lollypops, wineballs, ice cream cones, and sugared cookies in fingers sticky and gummy,

And they've held balls and bats and gloves and marbles and jack-knives and slingshots and spinning tops in the thrill of sport and play,

And pennies and nickels and dimes and quarters and sometimes on New Year's, Easter, Lincoln's Birthday, May Day, a brand new green dollar bill,

They've held pens and rulers and maps and books in palms spotted and smeared with ink,

And they've held dice and cards and half-pint flasks and cue sticks and cigars and cigarettes in the pride of new maturity . . .

II

I am black and I have seen black hands, millions and millions of them --

They were tired and awkward and calloused and grimy and covered with hangnails,

And they were caught in the fast-moving belts of machines and snagged and smashed and crushed,

And they jerked up and down at the throbbing machines massing taller and taller the heaps of gold in the banks of the bosses,

And they piled higher and higher the steel, iron, the lumber, wheat, rye, the oats, corn, the cotton, the wool, the oil, the coat, the meat, the fruit, the glass, and the stone until there was too much to be used,

And they grabbed guns and slung them on their shoulders and marched and groped in trenches and fought and killed and conquered nations who were customers for the goods black hands made.

And again black hands stacked goods higher and higher until there was too much to be used,

And then the black hand held trembling at the factory gates the dreaded lay-off slip,

And the black hands hung idle and swung empty and grew soft and got weak and bony from unemployment and starvation,

And they grew nervous and sweaty, and opened and shut in anguish and doubt and hesitation and irresolution . . .

III

I am black and I have seen black hands, millions and millions of them --

Reaching hesitantly out of days of slow death for the goods they had made, but the bosses warned that the goods were private and did not belong to them,

And the black hands struck desperately out in defense of life and there was blood, but the enraged bosses decreed that this too was wrong,

And the black hands felt the cold steel bars of the prison they had made, in despair tested their strength and found that they could neither bend nor break them,

And the black hands fought and scratched and held back but a thousand white hands took them and tied them,

And the black hands lifted palms in mute and futile supplication to the sodden faces of mobs wild in the reveries of sadism,

And the black hands strained and clawed and struggled in vain at the noose that tightened about the black throat,

And the black hands waved and beat fearfully at the tall flames that cooked and charred the black flesh . . .

IV

I am black and I have seen black hands

Raised in fists of revolt, side by side with the white fists of white workers,

And some day -- and it is only this which sutains me --

Someday there shall be millions and millions of them,

On some red day in a burst of fists on a new horizon!

"Between the World and Me"

And one morning while in the woods I stumbled

suddenly upon the thing,

Stumbled upon it in a grassy clearing guarded by scaly

oaks and elms

And the sooty details of the scene rose, thrusting

themselves between the world and me....

There was a design of white bones slumbering forgottenly

upon a cushion of ashes.

There was a charred stump of a sapling pointing a blunt

finger accusingly at the sky.

There were torn tree limbs, tiny veins of burnt leaves, and

a scorched coil of greasy hemp;

A vacant shoe, an empty tie, a ripped shirt, a lonely hat,

and a pair of trousers stiff with black blood.

And upon the trampled grass were buttons, dead matches,

butt-ends of cigars and cigarettes, peanut shells, a

drained gin-flask, and a whore's lipstick;

Scattered traces of tar, restless arrays of feathers, and the

lingering smell of gasoline.

And through the morning air the sun poured yellow

surprise into the eye sockets of the stony skull....

And while I stood my mind was frozen within cold pity

for the life that was gone.

The ground gripped my feet and my heart was circled by

icy walls of fear--

The sun died in the sky; a night wind muttered in the

grass and fumbled the leaves in the trees; the woods

poured forth the hungry yelping of hounds; the

darkness screamed with thirsty voices; and the witnesses rose and lived:

The dry bones stirred, rattled, lifted, melting themselves

into my bones.

The grey ashes formed flesh firm and black, entering into

my flesh.

The gin-flask passed from mouth to mouth, cigars and

cigarettes glowed, the whore smeared lipstick red

upon her lips,

And a thousand faces swirled around me, clamoring that

my life be burned....

And then they had me, stripped me, battering my teeth

into my throat till I swallowed my own blood.

My voice was drowned in the roar of their voices, and my

black wet body slipped and rolled in their hands as

they bound me to the sapling.

And my skin clung to the bubbling hot tar, falling from

me in limp patches.

And the down and quills of the white feathers sank into

my raw flesh, and I moaned in my agony.

Then my blood was cooled mercifully, cooled by a

baptism of gasoline.

And in a blaze of red I leaped to the sky as pain rose like water, boiling my limbs

Panting, begging I clutched childlike, clutched to the hot

sides of death.

Now I am dry bones and my face a stony skull staring in

yellow surprise at the sun....

Friday, August 5, 2011

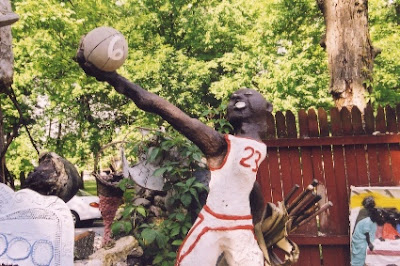

Charles Smith Exhibit Opens at DuSable Museum

"I'm going into the heart of mankind - Blacks, Whites, Hispanics - wherever ignorance separates us I want to be there. My art is that of Dr. Martin Luther King... having a dream, a vision, and a hope for our people and place in this world with respect, where one is judged by character not color."

An exhibit featuring the sculpture of Charles Smith opens today at the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago.

Smith was born in New Orleans and raised in the Chicago area. He was deeply affected by the death and open-casket funeral of Emmett Till, a young man also from Chicago close to his own age who was brutally murdered while visiting relatives in Mississippi in 1955.

Smith served in the Marines in Viet Nam, receiving a Purple Heart. When he returned he felt a call to portray and uplift the African American experience through sculpture. He says, "God gave me a weapon -- use art."

The yard of his Aurora home was transformed into the African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archives, a display of monuments honoring civil rights leaders, musicians, artists, athletes and old friends. He also created memorials to the 4000 African American troops who died in Viet Nam and to the massacred in Rwanda.

In 2002 Smith returned to Louisiana to create a similar museum in Hammond, and to participate in the Algiers Folk Art Zone in New Orleans.

The exhibit runs through December 31.

An exhibit featuring the sculpture of Charles Smith opens today at the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago.

Smith was born in New Orleans and raised in the Chicago area. He was deeply affected by the death and open-casket funeral of Emmett Till, a young man also from Chicago close to his own age who was brutally murdered while visiting relatives in Mississippi in 1955.

Smith served in the Marines in Viet Nam, receiving a Purple Heart. When he returned he felt a call to portray and uplift the African American experience through sculpture. He says, "God gave me a weapon -- use art."

The yard of his Aurora home was transformed into the African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archives, a display of monuments honoring civil rights leaders, musicians, artists, athletes and old friends. He also created memorials to the 4000 African American troops who died in Viet Nam and to the massacred in Rwanda.

In 2002 Smith returned to Louisiana to create a similar museum in Hammond, and to participate in the Algiers Folk Art Zone in New Orleans.

The exhibit runs through December 31.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Emmett Till

"Be careful. If you have to get down on your knees and bow when a white person goes past, do it willingly." ~ Mamie Till Bradley

Chicagoan Emmett Till was 14 years old when he was brutally murdered while visiting relatives in the Mississippi Delta for allegedly whistling at a white woman. The following publicity made this the most widely known lynching of the twentieth century. Outrage felt by African Americans across the country was one of the causes leading to the civil rights movement, with the Rosa Parks-inspired Montgomery bus boycott beginning only months later.

Till was born July 25, 1941 to Mamie Cauthon Till from Webb, Mississippi, and Louis Till. His parents separated when he was two, and Mrs. Till married Pink Bradley in 1951, divorcing him a year later. In the summer of 1955 Mrs. Till's uncle Mose Wright was in Chicago and he took young Emmett back with him for a visit to the Delta. Mrs. Bradley was reluctant to let her son go, warning him of the differences between her home state and the life he knew in Chicago.

Till, along with his cousins and other teenagers, went to Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market on August 24 in Money, Mississippi, a town of only 55 people. Carolyn Bryant was working alone at the counter of the store, which catered to sharecroppers and their families. Descriptions of what happened next vary, but witnesses agree that the other boys dared Till to flirt with Mrs. Bryant. It is reported that as he left the store some heard him whistle at her. However, Till had a stutter that he could overcome by whistling. The youths left the area quickly and were afraid to tell Mose Wright what had happened.

Mississippi—1955 (1955)

by Langston Hughes

Oh what sorrow!

Oh what pity!

Oh, what pain

That tears and blood

Should mix like rain

And terror come again

To Mississippi.

Come again?

Where has terror been?

On vacation? Up North?

In some other section

Of the nation,

Lying low, unpublicized?

Masked—with only

Jaundiced eyes

Showing through the mask?

Oh, what sorrow,

Pity, pain,

That tears and blood

Should mix like rain

In Mississippi!

And terror, fetid hot,

Yet clammy cold

Remain.

Chicagoan Emmett Till was 14 years old when he was brutally murdered while visiting relatives in the Mississippi Delta for allegedly whistling at a white woman. The following publicity made this the most widely known lynching of the twentieth century. Outrage felt by African Americans across the country was one of the causes leading to the civil rights movement, with the Rosa Parks-inspired Montgomery bus boycott beginning only months later.

Till was born July 25, 1941 to Mamie Cauthon Till from Webb, Mississippi, and Louis Till. His parents separated when he was two, and Mrs. Till married Pink Bradley in 1951, divorcing him a year later. In the summer of 1955 Mrs. Till's uncle Mose Wright was in Chicago and he took young Emmett back with him for a visit to the Delta. Mrs. Bradley was reluctant to let her son go, warning him of the differences between her home state and the life he knew in Chicago.

Till, along with his cousins and other teenagers, went to Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market on August 24 in Money, Mississippi, a town of only 55 people. Carolyn Bryant was working alone at the counter of the store, which catered to sharecroppers and their families. Descriptions of what happened next vary, but witnesses agree that the other boys dared Till to flirt with Mrs. Bryant. It is reported that as he left the store some heard him whistle at her. However, Till had a stutter that he could overcome by whistling. The youths left the area quickly and were afraid to tell Mose Wright what had happened.

Carolyn's husband Roy was out of town at the time. After he returned several days later he and his half-brother J. W. Milam went to Wright's cabin in the early morning hours of Sunday, August 28 and forcibly took Till away with them. They beat Till, then shot him in the head and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River tied to a 70-pound fan from a cotton gin.

Till's badly disfigured body was discovered three days later. When questioned, Bryant and Milam admitted they had taken Till from his great-uncle's house but had let him go. They were later indicted for murder by the Tallahatchie County Grand Jury. Local press coverage at first expressed shame and anger but quickly turned defensive as the story spread across the nation. Mamie Till Bradley had her son's body sent back to Chicago and insisted on an open-casket viewing. Very graphic photographs were published in Jet magazine and The Chicago Defender.

|

| Jury seated on first two rows. |

Bryant and Milam's trial began less than a month later on September 19. The defense claimed that the body could not be positively identified. Both were acquitted a week later after an hour's deliberation by the all-male, all-white jury. In an interview with Look magazine the next year they admitted that they killed Till, with Milam saying "Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless.... 'Chicago boy,' I said, 'I'm tired of 'em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I'm going to make an example of you—just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.'"

In addition to global media coverage of the case and the wider issues of justice for African Americans, it has appeared in a number of literary works, including Bebe Moore Campbell's novel Your Blues Ain't Like Mine, Toni Morrison's play Dreaming Emmett, and poems Afterimages by Audre Lorde, A Bronzeville Mother Loiters In Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon by Gwendolyn Brooks and Mississippi 1955 by Langston Hughes.

by Langston Hughes

Oh what sorrow!

Oh what pity!

Oh, what pain

That tears and blood

Should mix like rain

And terror come again

To Mississippi.

Come again?

Where has terror been?

On vacation? Up North?

In some other section

Of the nation,

Lying low, unpublicized?

Masked—with only

Jaundiced eyes

Showing through the mask?

Oh, what sorrow,

Pity, pain,

That tears and blood

Should mix like rain

In Mississippi!

And terror, fetid hot,

Yet clammy cold

Remain.

Saturday, July 16, 2011

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Our country's national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob.

An outspoken crusader against lynching and one of the founders of the NAACP, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, 35 miles southwest of Memphis. She attended a local Freedman's School which is now Rust College, but dropped out to support her younger brothers and sisters by teaching after their parents died of yellow fever. She earned $30 per month although white teachers in the area were paid $80. With three younger sisters, she soon moved to Memphis where she taught and attended summer classes at Fisk University.

In 1884 she refused to move to a "Jim Crow" car on a Chesapeake & Ohio train, and was dragged from the train by the conductor and two other men while white passengers cheered. She sued the railroad and was awarded $500 in damages; the decision was overturned by the Tennessee State Supreme Court.

While teaching, she began to write about race relations for the Free Speech and Headlight, a Memphis anti-segregation newspaper, and other publications. She later became editor and co-owner of the paper. In 1892 while she was in Natchez selling newspaper subscriptions, a local grocery store owned by three African American men was attacked by white men who were resentful of its success. The owners defended the store and were arrested for shooting three of the invaders. Once in jail, they were taken out and killed.

Mrs. Wells-Barnett wrote about the lynching, and her articles appeared in newspapers across the country. She also urged African Americans to leave Memphis or, if they stayed, to boycott white businesses. She began to research lynchings and published a pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases setting forth her finding that most were a result of minor infractions of the law or to eliminate business competition. Few were in response to rape, despite the popular belief, and she stated that most inter-racial sex was consensual. While on another out-of-town trip, the offices of the Free Speech and Headlight were destroyed, and instead of returning to Memphis she settled in Chicago.

An outspoken crusader against lynching and one of the founders of the NAACP, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, 35 miles southwest of Memphis. She attended a local Freedman's School which is now Rust College, but dropped out to support her younger brothers and sisters by teaching after their parents died of yellow fever. She earned $30 per month although white teachers in the area were paid $80. With three younger sisters, she soon moved to Memphis where she taught and attended summer classes at Fisk University.

In 1884 she refused to move to a "Jim Crow" car on a Chesapeake & Ohio train, and was dragged from the train by the conductor and two other men while white passengers cheered. She sued the railroad and was awarded $500 in damages; the decision was overturned by the Tennessee State Supreme Court.

While teaching, she began to write about race relations for the Free Speech and Headlight, a Memphis anti-segregation newspaper, and other publications. She later became editor and co-owner of the paper. In 1892 while she was in Natchez selling newspaper subscriptions, a local grocery store owned by three African American men was attacked by white men who were resentful of its success. The owners defended the store and were arrested for shooting three of the invaders. Once in jail, they were taken out and killed.

Mrs. Wells-Barnett wrote about the lynching, and her articles appeared in newspapers across the country. She also urged African Americans to leave Memphis or, if they stayed, to boycott white businesses. She began to research lynchings and published a pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases setting forth her finding that most were a result of minor infractions of the law or to eliminate business competition. Few were in response to rape, despite the popular belief, and she stated that most inter-racial sex was consensual. While on another out-of-town trip, the offices of the Free Speech and Headlight were destroyed, and instead of returning to Memphis she settled in Chicago.

With other leaders such as Frederick Douglass, she organized a boycott of the Chicago World's Fair and continued her research, publishing The Red Record. She wrote for the Chicago Conservator, the oldest African American newspaper in the city, and in 1895 married its former editor, Ferdinand L. Barnett, an Assistant State Attorney.

While raising a family of four children, she continued to crusade against lynching, traveling throughout the United States and Great Britain. She also worked to improve living conditions in Chicago, and with Jane Addams blocked the segregation of the city's schools. In 1909 she was one of two African American women to sign "The Call", leading to the founding of the NAACP.

"I had an instinctive feeling that the people who have little or no school training should have something coming into their homes weekly which dealt with their problems in a simple, helpful way... so I wrote in a plain, common-sense way on the things that concerned our people."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)